- Explaining our 2022-23 economy forecast differences

- Explaining our 2022-23 fiscal forecast differences

- Refining our forecasts

- Introduction

- Market assumptions

- Inflation

- Box 2.1: Why has recent inflation been stronger than we forecast?

- Real GDP

- Box 2.2: Why has real household disposable income been stronger than forecast?

- Labour market and productivity

- Nominal GDP

- Introduction

- The evolution of our borrowing forecast for 2022-23

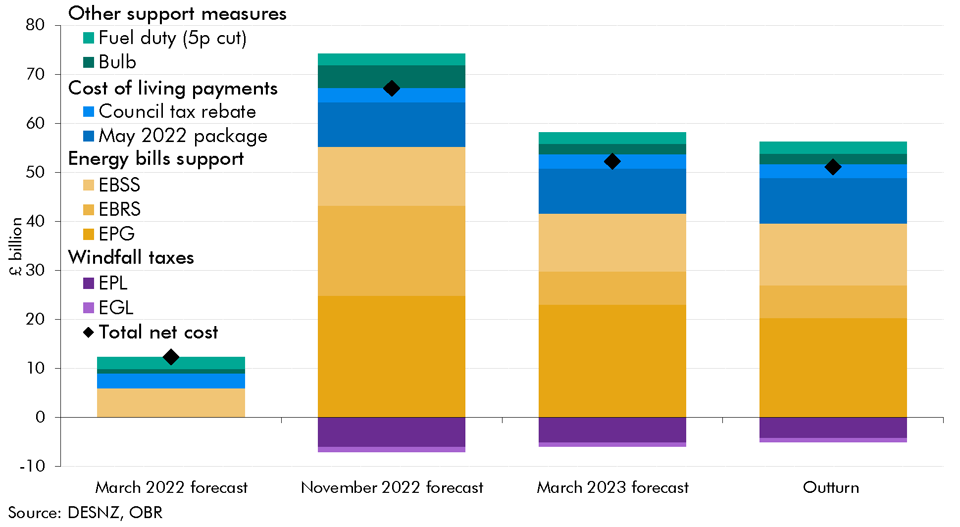

- Box 3.1: The cost of the Government’s energy support policies

- Introduction

- Lessons learnt

- Review of forecasting models

Foreword

The Office for Budget Responsibility was created in 2010 to provide independent and authoritative analysis of the UK public finances. Twice a year – usually at the time of each Budget and Autumn or Spring Statement – we publish a set of forecasts for the economy and public finances over the coming five years in our Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO). We use these forecasts to assess the Government’s progress against its fiscal targets.

In each EFO, we stress the uncertainty that lies around all such forecasts. We compare our central forecasts to those of other forecasters. We highlight the limited confidence that should be placed in our central forecast given the scale of shocks that inevitably drive a wedge between any central predictions and subsequent outcomes. We use sensitivity and scenario analysis to show how the public finances could be affected by alternative economic outcomes. And we highlight the residual uncertainties in the public finances, even if one were confident about the path for the economy – for example, because of uncertain estimates of the cost of policy measures.

Notwithstanding these uncertainties, we believe that it is important to set out our forecast in detail. It is also important to examine regularly how our forecasts compare to outturn data and to explain any discrepancies so that we can learn from our experience.

Our annual Forecast evaluation report enables us to reflect on the reasons for divergence between our central forecast and the subsequent outturns. To a significant extent these differences between outturns and previous forecasts are inevitable given the inherent difficulty in forecasting the path of the economy and the consequent effect on the public finances, which has been amplified recently by unforecastable shocks that hit the economy. But some differences are due to genuine errors, which would have been corrected before the forecast was finalised if we had spotted them. When we identify them, we describe them as such. Errors of this sort are inevitable from time to time in a highly disaggregated forecasting exercise like ours.

This year our report analyses the performance of our March 2021 and March 2022 economic forecasts for the 2022-23 financial year. Over this period, higher energy, food and other prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to a moderation in real demand and higher inflation than expected.

This year, we have also published a working paper taking a comprehensive look at our overall forecasting record since the OBR was established in 2010. It compares our economic and fiscal forecasts against those of external UK forecasters, the Bank of England, other official forecasters in Europe, and the official UK forecasts produced by the Treasury during the 20 years before the OBR was established. [1] The direction of forecast differences examined in this FER mirror those identified in that more comprehensive piece of analysis, namely a tendency to overestimate real GDP growth and underestimate government borrowing.

We provided a final copy of this report to the Treasury two working days in advance of publication. This timing was extended in recent changes to our Memorandum of Understanding with HM Treasury and our main forecasting departments.

The Budget Responsibility Committee

Richard Hughes, Professor David Miles CBE and Tom Josephs

Chapter 1: Executive summary

1.1 The focus of this year’s Forecast evaluation report (FER) is the performance of our forecasts for the financial year 2022-23. The almost unprecedented fall and recovery in the economic activity caused by the covid pandemic in the previous two years, was followed in 2022-23 by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The war led to a spike in global gas (and oil) prices that compounded UK inflationary pressures that had already been building due to supply bottlenecks and a tightening labour market in the wake of the pandemic.

1.2 Against this backdrop, our March 2021 forecast (made a year before the Russian invasion) and March 2022 forecast (made within a few weeks of the invasion) significantly underestimated the strength and persistence of inflation, and overestimated the level of economic activity. The upward surprise in inflation greatly exceeded the shortfall in GDP and led to nominal GDP growth – the key determinant of tax receipts – outpacing both March forecasts. This led to significantly higher nominal tax receipts than we had expected. But higher inflation and the associated fiscal and monetary policy response, in the form of welfare and energy costs support and higher Bank Rate, pushed up spending and debt interest by even more. As a result, we underestimated borrowing in 2022-23 which, at £128.4 billion (5.1 per cent of GDP) was £21.5 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP) above our March 2021 and £29.3 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP) above March 2022 forecasts.

Explaining our 2022-23 economy forecast differences

Inflation

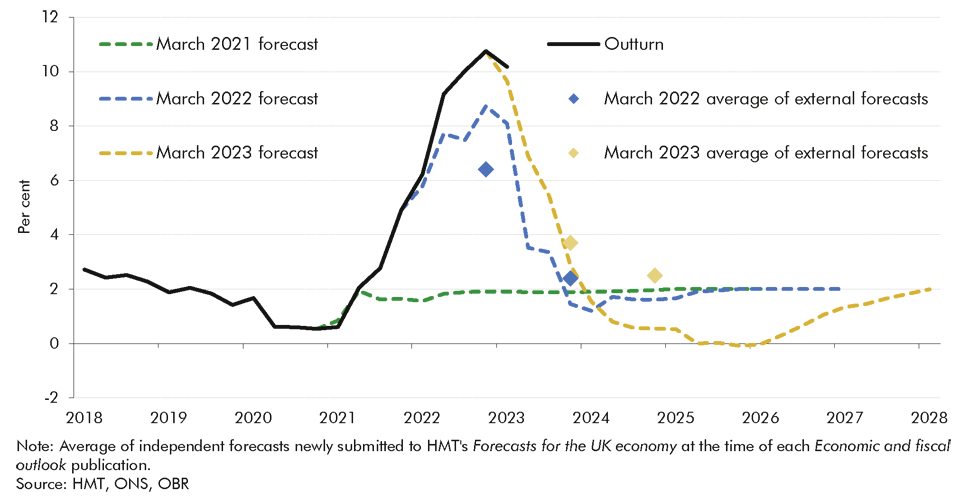

1.3 The extent of the CPI inflation overshoot in 2022-23 is the largest difference between forecast and outturn since the OBR began forecasting in 2010 (Chart 1.1). CPI inflation was 8.2 percentage points higher than we forecast in March 2021 and 2.0 percentage points higher than our March 2022 forecast. We identified in our January 2023 Forecast evaluation report (FER) several explanations for this overshoot including: an unexpectedly strong recovery in demand in advanced economies, pushing up against persistent supply and logistics bottlenecks; rising energy costs; and a tighter post-pandemic labour market than we had anticipated. In this FER we have re-considered our assumptions about the speed and size of pass-through of higher energy prices into wider consumer prices, which our latest analysis now suggests have also been too low.

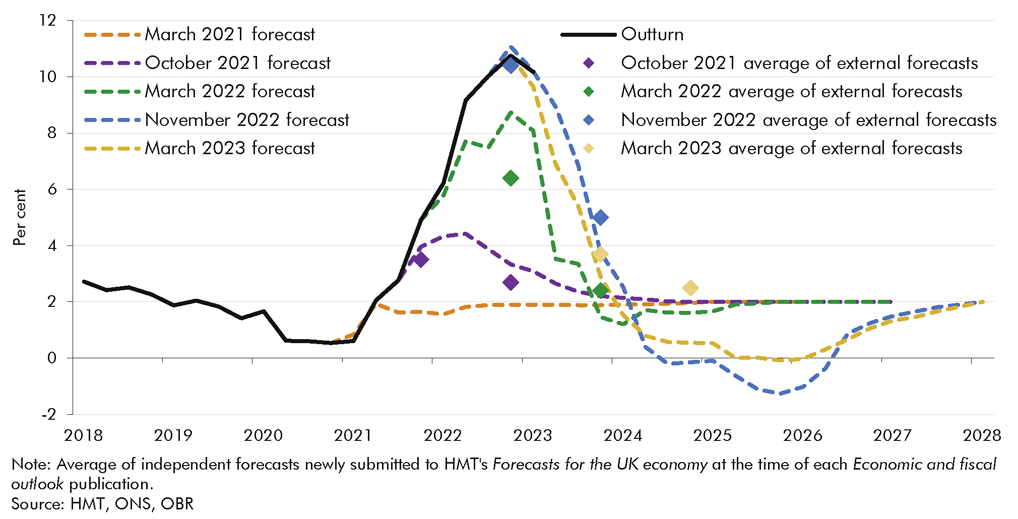

Chart 1.1: Successive inflation forecasts

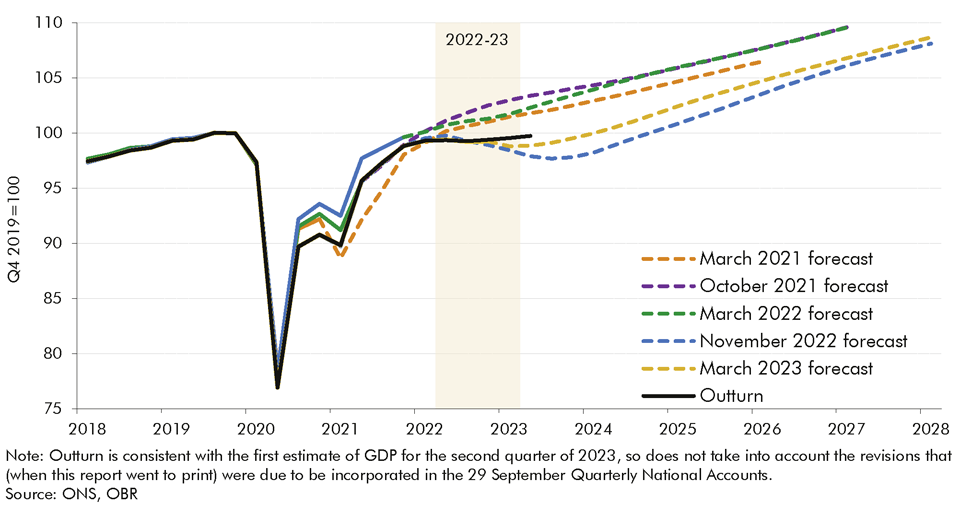

GDP

1.4 Based on ONS estimates available at the time of writing this report, our March 2021 and 2022 forecasts overestimated real GDP growth in 2022-23 by 3.3 and 0.6 percentage points respectively, as rising energy prices and global supply bottlenecks weighed on UK productivity. [2] The associated increase in consumer prices has eroded real wages and led to much larger increases in interest rates than financial markets expected, which have reduced growth in consumption and investment relative to our forecasts. Living standards, as measured by real household disposable income per capita, fell by 1.9 per cent in 2022-23, the largest fall in any single financial year since ONS records began in 1956-57. This was a much worse outcome than the 0.8 per cent rise anticipated in our March 2021 forecast but close to the 2.2 per cent fall expected in our March 2022 forecast.

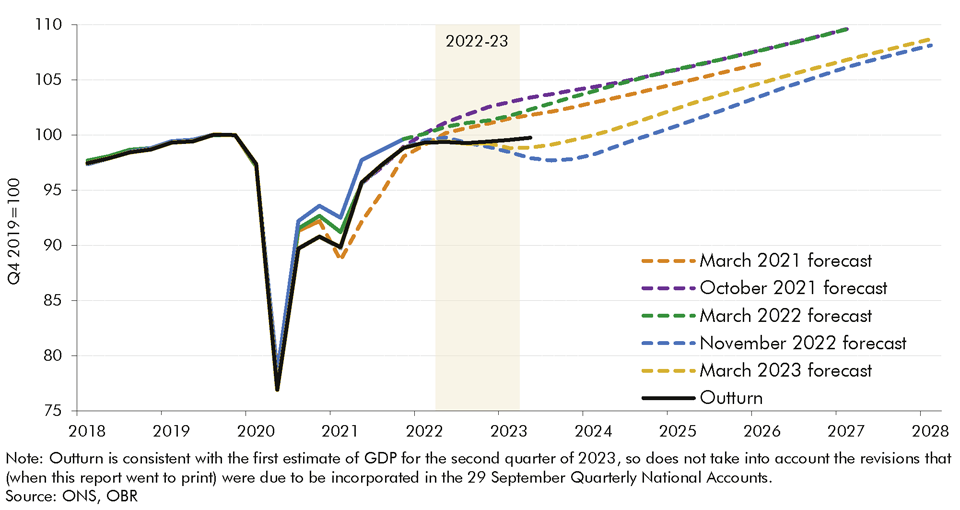

Chart 1.2: Successive forecasts for the level of real GDP

Labour market and productivity

1.5 Labour supply growth in 2022-23, measured in terms of total hours worked, was 2.2 and 0.6 percentage points less than estimated in both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. This undershoot mainly reflects a significant overestimation of average hours worked, which did not recover to pre-pandemic levels as swiftly as had been expected following the closure of the furlough scheme. The outturn for annual employment growth in 2022-23 was 0.3 and 0.1 percentage points higher than expected in the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. This resulted in the unemployment rate falling faster than expected, undershooting both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts by 2.0 and 0.3 percentage points respectively.

1.6 Productivity growth was 1.2 percentage points weaker than expected in the March 2021 forecast, which overestimated GDP growth by 3.3 percentage points in 2022-23 but total hours growth by only 2.2 percentage points. Both were revised lower in the March 2022 forecast, which predicted no growth in productivity, and ended up much closer to the 0.1 per cent outturn. The weakness in productivity growth over the year suggests that the post-pandemic rebound in total factor productivity may not have been as strong as expected.

Nominal GDP

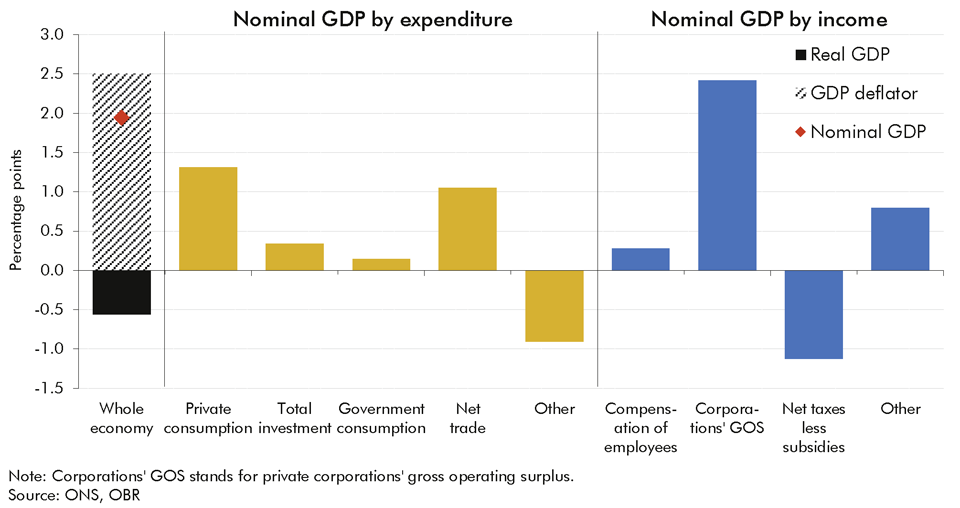

1.7 Stronger-than-expected growth in the GDP deflator meant our March 2021 forecast underestimated cumulative growth in nominal GDP from 2020-21 to 2022-23, despite cumulative real GDP growth turning out weaker than expected. The surprise was driven by much stronger growth in nominal consumption (contributing 5.1 percentage points of the total difference of 8.3 percentage points) supported on the income side by stronger-than-expected growth in employees’ compensation (5.1 percentage points higher).

1.8 A similar story holds for our March 2022 forecast, with higher inflation outweighing weaker real GDP growth. Nominal consumption again accounts for most of the additional growth (1.3 out of 1.9 percentage points), but this time on the income side the forecast difference is more than explained by much stronger-than-anticipated growth in corporate profits (as measured in the National Accounts).

Explaining our 2022-23 fiscal forecast differences

1.9 These nominal GDP surprises provide a partial explanation for government borrowing in 2022-23 coming in £21.5 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP) above our March 2021 forecast and £29.3 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP) above our March 2022 forecast. For both our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, higher-than-expected receipts were more than offset by higher-than-expected spending, resulting in higher borrowing by the end of the financial year.

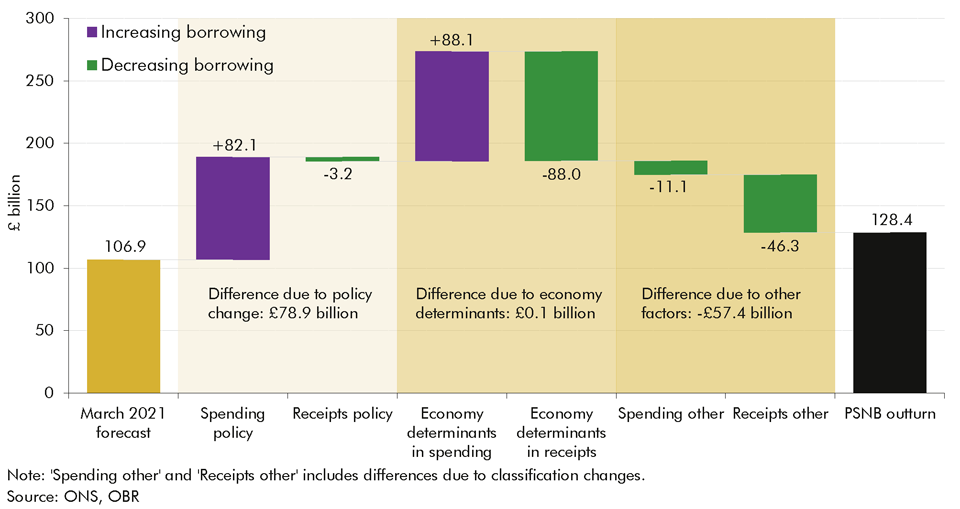

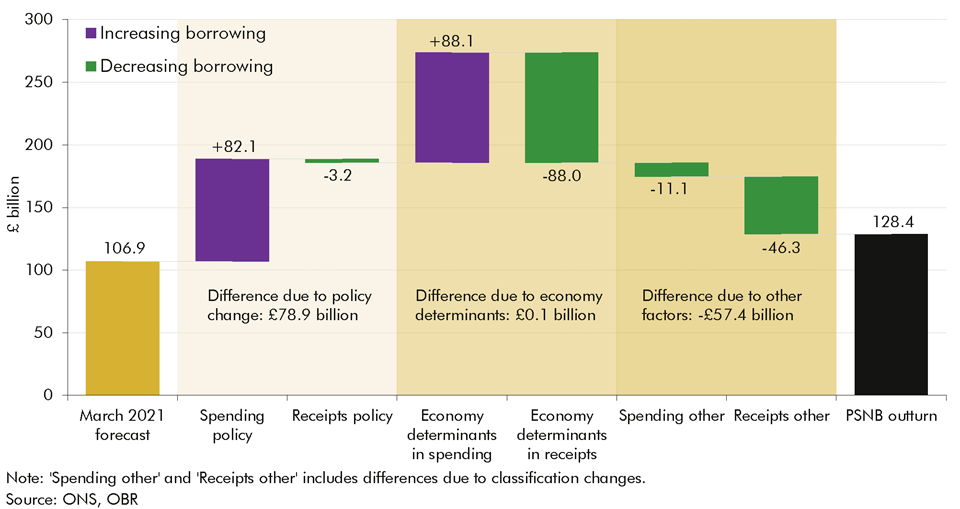

March 2021 borrowing forecast

1.10 Against our March 2021 forecast, borrowing came in £21.5 billion higher than expected. Of this overall difference (summarised in Chart 1.3):

- Economic factors were neutral with large differences in tax receipts (£88.0 billion) and spending (£88.1 billion) almost exactly offsetting each other. Both effects are in large part due to higher-than-anticipated inflation.

- Policy changes drove up borrowing by £78.9 billion due primarily to the Energy Price Guarantee and other support provided to help households and businesses to cope with the sudden rise in the cost of energy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Other factors reduced borrowing by £57.4 billion. These factors drive a £46.3 billion underestimate of receipts, including due to differences in the effective tax rate of corporation tax, and a £11.1 billion overestimate in spending.

Chart 1.3: March 2021 PSNB error for 2022-23 by source

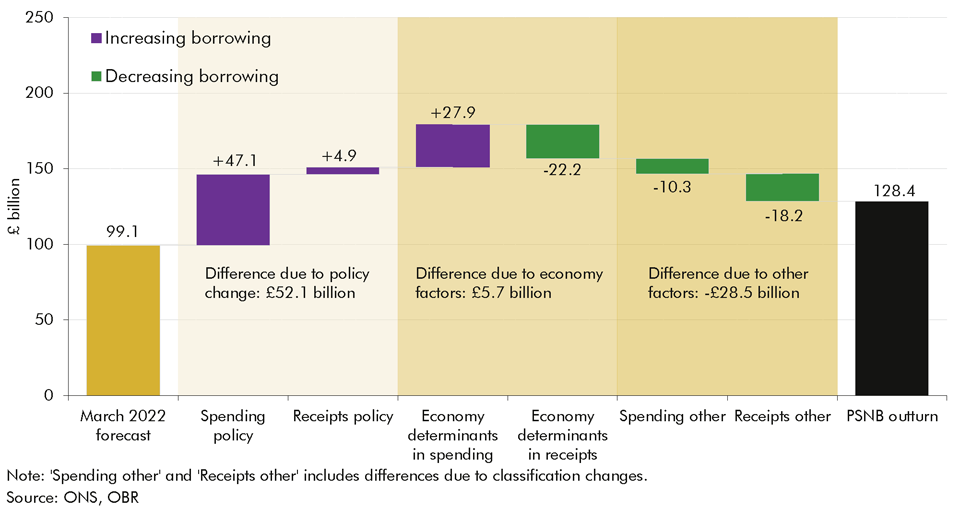

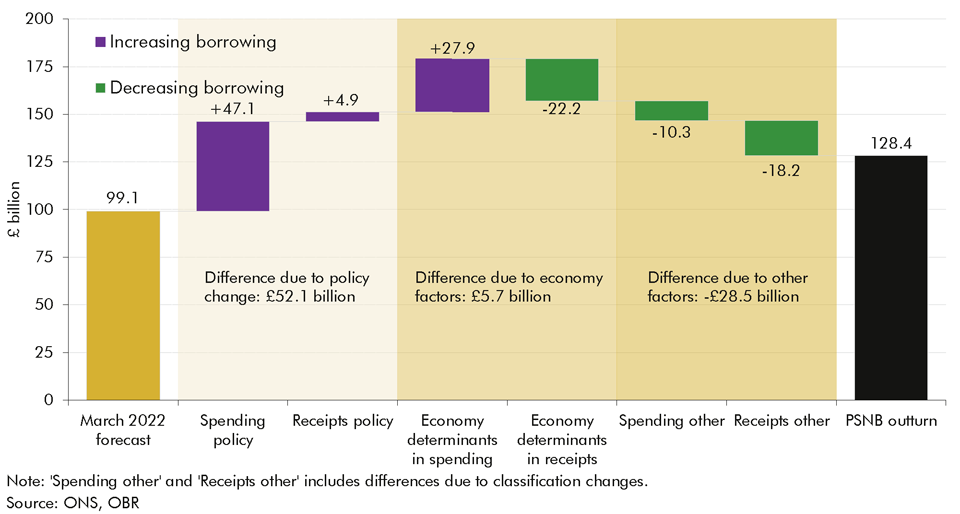

March 2022 borrowing forecast

1.11 Our March 2022 forecast also underestimated borrowing by £29.3 billion. Of this overall difference (summarised in Chart 1.4):

- Economic factors make up £5.7 billion of the overall PSNB error. £27.9 billion of the difference was due to higher spending – mainly from the underestimate of the inflation uplift acting on index-linked government debt and Bank Rate on payments made from the Asset Purchase Facility. This was partly offset by £22.2 billion of underestimated receipts from faster growth in tax bases and lower welfare spending (£0.6 billion).

- Policy changes make up £52.1 billion of total PSNB error. £47.1 billion (90 per cent) was due to new spending policies – particularly on energy support schemes and cost-of-living payments (£8.4 billion). £4.9 billion was due to lower receipts, in particular the cancellation of NICs rate rise after 7 months.

- Other factors reduced borrowing by £28.5 billion: £10.3 billion lower spending than anticipated and £18.2 billion higher receipts. The unexplained receipts overshoot was mostly in onshore corporation tax where the effective tax rate has been much stronger than anticipated in March 2022’s forecast.

Chart 1.4: March 2022 PSNB error for 2022-23 by source

Public sector net debt

1.12 The level of public sector net debt (PSND) was 98.0 per cent of GDP in 2022-23. This was 10.4 percentage points lower than forecast in March 2021 but 2.5 percentage points above our March 2022 forecast. This reflects:

- Nominal GDP, which was £176.7 billion (7.3 per cent) higher than expected in March 2021 and contributed around 7.4 percentage points of the undershoot. Our March 2022 forecast underestimated nominal GDP by £20.4 billion, reducing the size of the overall overshoot by 0.8 percentage points.

- Cash debt at the end of 2021-22 was £117.7 billion lower than forecast in March 2021, representing 4.5 percentage points of the undershoot relating to that forecast. It was £52.8 billion higher than forecast in March 2022, 2.0 percentage points of the overshoot.

- Debt accumulation through 2022-23 was higher than forecast in both March 2021 and March 2022, raising debt relative to both forecasts by 1.5 and 1.2 percentage points respectively.

Refining our forecasts

1.13 As was the case with the Covid pandemic, forecasting the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was always likely to be challenging, given the lack of recent historical precedent to draw on. In terms of how we responded to these shocks and the lessons we can learn:

- For our economy forecast, we have re-examined the effect of previous historical energy price shocks on inflation. The UK economy is much less energy intensive than at the time of the last extreme rises in energy prices in the 1970s. While our forecasts took that into account, it seems that the indirect effect of energy prices on inflation may have been greater than we expected. We will incorporate the evidence of this stronger energy price pass through in our November 2023 forecast. The relative resilience of real household disposable income has also prompted us to review the pass-through of rises in Bank Rate to household disposable incomes.

- On the fiscal side, the main 2022-23 forecast differences can be explained by economic factors. Of the remaining differences, the key lessons learnt are:

- The receipts overshoot against both the March 2021 and 2022 forecasts reinforces the importance of looking at nominal as well as real economy trends. In-year receipts have recently been stronger than indicated by latest data for key nominal tax bases, particularly for onshore corporation tax. Early ONS data on profits is very provisional, so we have put more focus on sectoral trends and the source of differences (e.g. payments from very large companies compared with those from small companies).

- The October 2021 Spending Review led to a £39.5 billion (1.6 per cent of GDP) increase in our departmental spending forecast. This has been a frequent source of difference between our spending forecasts and outturn, caused when governments replace the indicative aggregate spending plans with detailed department-by-department spending limits at Spending Reviews. We will reflect on the implications of this pattern of government behaviour in our upcoming November 2023 EFO.

1.14 We also undertake an annual review of our economic and fiscal forecasting models. This year, on the economic side, we have focussed on improving our inflation modelling by enhancing the range of statistical models to produce our short-term forecast and our medium-term models for tradables inflation and wage growth. On the fiscal side we have published an updated ‘model assessment database’ on our website alongside this FER, which reviews progress against previously identified priorities, and outlines new priorities for 2023. Those priorities include a deeper understanding of the self-assessment income tax base, and the development of a new onshore corporation tax model for our November 2023 forecast, given that receipts have been much stronger than expected.

Chapter 2: The economy

Introduction

2.1 This chapter assesses the performance of our March 2021 and March 2022 economic forecasts for the 2022-23 financial year, a period that saw the UK economy suffer the consequences of the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and associated rise in energy, food, and other prices.

2.2 Our March 2021 forecast was finalised one year before the invasion of Ukraine (and 8 months before Russia began to tighten its gas supplies to Europe) and can therefore be thought of as a counterfactual for what might have happened if the invasion had not taken place. Many of the most significant differences between this pre-invasion forecast and outturn therefore represent the consequences of the invasion itself.

2.3 Our March 2022 forecast was finalised 22 days after the Russian invasion began and therefore represents our initial attempt to predict its economic consequences for the UK. The differences between this initial post-invasion forecast and outturn partly reflects what we, and everyone, subsequently learned about the duration and magnitude of the ensuing war; the severity of sanctions placed by the international community on Russia in response; how these and other factors influenced the paths of global energy, food, and other tradable goods prices and interest rates; their consequences for domestic inflation and economic activity; and the Government’s policy response.

2.4 In evaluating the performance of these two economic forecasts for 2022-23, the chapter explores the differences between our forecast and the latest outturn data for: [3]

- market-derived assumptions, including interest rates, gas and oil prices, equity prices, and the exchange rate;

- the rate of inflation and its components, including the price of energy, other tradable and non-tradable items (Box 2.1);

- the rate and composition of real GDP growth;

- household disposable income and its components (Box 2.2);

- the labour market and productivity; and

- the rate and composition of nominal GDP growth, a key fiscal forecast determinant.

Market assumptions

2.5 Table 2.1 compares the market assumptions from our March 2021 and 2022 forecast with outturns for 2022-23:

- Gas prices were 5 times higher in 2022-23 than we estimated in our March 2021 forecast, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 drove prices to their highest level on record in the third quarter of 2022. Our March 2022 forecast reflects market expectations in the first quarter of 2022, when there were serious concerns about limited gas supplies and European storage capacity. A warmer-than-expected winter in Europe and surge in liquified natural gas imports from the US and Middle East eased concerns slightly, and our March 2022 forecast ended up overestimating gas prices by £0.60 per therm (19 per cent).

- Oil prices were almost double our March 2021 forecast and remained slightly higher than expected in March 2022. As oil is a globally traded commodity, European prices were less sensitive to the disruption in Russian supply than gas, which depends heavily on regional pipeline networks. Nonetheless, the impact of OPEC cuts to production and the EU ban on Russian oil in December 2022 pushed 2022-23 oil prices above expectations in both our March 2021 and 2022 forecasts.

- Bank Rate averaged 2.3 per cent in 2022-23, exceeding our March 2021 and March 2022 forecast expectations by 2.3 and 0.9 percentage points respectively. This came as the Bank of England responded to increased inflationary pressures, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and growing supply constraints (as discussed in Box 2.1).

- Gilt rates were 2.0 and 1.5 percentage points higher than expected in our March 2021 and 2022 forecasts, reflecting rising global interest rates, higher-than-expected Bank Rate, and a spike in yields following the announcement of the 23 September growth plan – seemingly reflecting UK-specific factors that have since unwound.

- Quantitative easing, reflecting the stock of assets held in the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) in 2022-23, was £56.9 billion less than we assumed in our March 2021 forecast, which assumed the Bank reinvested remaining gilts rather than letting the APF run down. Our March 2022 forecast was also £19.8 billion above outturn, as it assumed only ‘passive’ runoff, rather than ‘actively’ selling gilts before they redeemed as has taken place since November 2022.

- The effective exchange rate was broadly in line with our March 2021 forecast, but came in 4.3 per cent below our March 2022 forecast despite a rising interest rate, reflecting the slowdown in the economy. The exchange rate also fell following the announcement of the 23 September Growth Plan, but like gilt prices, then recovered.

Table 2.1 Market-derived assumptions for 2023-23, financial year average

| Bank rate (per cent) | Market gilt rates (per cent) | Oil price ($ per barrel) | Gas price (£ per therm) | Quantitative easing (1) (£ billion) | Equity prices (FTSE All-share) | Exchange rate (index) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2021 forecast | 0.05 | 1.19 | 51.7 | 0.4 | 874.9 | 4,150 | 79.5 |

| March 2022 forecast | 1.43 | 1.65 | 91.7 | 2.9 | 837.9 | 4,187 | 82.4 |

| Latest data | 2.31 | 3.18 | 95.2 | 2.4 | 818.1 | 4,089 | 78.9 |

| Difference (2) | |||||||

| March 2021 | 2.26 | 1.98 | 84.3 | 446.6 | -56.9 | -1.5 | -0.8 |

| March 2022 | 0.88 | 1.53 | 3.9 | -19.4 | -19.8 | -2.3 | -4.3 |

| 1) Total asset purchases, including corporate bonds, at the end of the 2022-23 financial year. 2) Per cent difference except Bank Rate and market gilt rates (percentage points) and quantitative easing (£ billion). |

2.6 These large increases in gas prices, oil prices, and interest rates in the space of less than 12 months are unprecedented in the 13 years in which the OBR has been forecasting the economy. Prior to the £1.30 per therm year-on-year increase in gas prices from 2020-21 to 2021-22, and £0.70 per therm increase seen from 2021-22 to 2022-23, the largest year-on-year increase was the £0.20 increase seen in 2008-09. And before the 2.1 percentage point increase in Bank rate in 2022-23, the largest change in rates was the 0.6 percentage point cut in 2020-21. Many of the differences between forecasts and outturn for the economic variables discussed below are a consequence of those large global shocks.

Inflation

Inflation in 2022-23

2.7 The Russian invasion of Ukraine, coupled with a growing mismatch between the global demand for and supply of tradable goods, pushed the overall rate of CPI inflation 8.2 percentage points higher than in our March 2021 forecast in 2022-23. Rather than being just below the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target as we forecast in March 2021, inflation averaged 10.0 per cent in 2022-23. As Table 2.2 shows, by the fourth quarter of 2022 inflation reached 10.7 per cent, its highest level in over 40 years. Our March 2022 forecast factored in pressure on energy prices from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, expecting inflation to peak at 8.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022, but even this was 2 percentage points lower than what eventually transpired.

Table 2.2 Inflation forecasts

| Percentage change on a year earlier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2022-23 annual average | ||||

| Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | |||

| CPI inflation | ||||||

| March 2021 forecast | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| March 2022 forecast | 7.7 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 8.0 | |

| Latest data | 9.2 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 10.0 | |

| Difference (1) | ||||||

| March 2021 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 8.2 | |

| March 2022 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| 1) Differences in percentage points. Totals may not sum due to rounding. |

2.8 Our March 2021 forecast underestimated all of the underlying inflation components shown in Table 2.3. A faster-than-expected post-pandemic recovery in goods demand in North America and Europe bumped up against supply constraints in Asia, pushing up the prices of tradable goods. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent imposition of sanctions pushed up European energy prices with knock-on effects for the price of UK utilities (including electricity and gas prices) and food, beverages and tobacco. The prices of domestically produced services were also higher than anticipated due to a combination of higher energy and other input costs; pressures for higher wage increases to offset at least some of the increased cost of living; and a larger-than-anticipated reduction in the size of the labour force in the aftermath of the pandemic, which put further upward pressure on wages. While our March 2022 forecast included our initial estimate of the impact of the Russian invasion on domestic prices, we still underestimated the inflation contributions from energy by 0.2 percentage points, food, beverages, and tobacco by 1.2 percentage points, tradable goods by 1 percentage point, and slightly overestimated other non-tradables inflation by 0.4 percentage points.

Table 2.3 Differences between outturn inflation contributions and our March 2021 and March 2022 inflation forecasts

| Percentage point contribution to annual CPI inflation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food, beverages and tobacco | Utilities | Fuels | Other tradables | Other non-tradables | Total | |

| March 2021 forecast | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| March 2022 forecast | 0.7 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 8.0 |

| Latest data | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 10.0 |

| Difference (1) | ||||||

| March 2021 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 8.2 |

| March 2022 | 1.2 | -0.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | -0.4 | 2.0 |

| 1) Differences in percentage points. Totals may not sum due to rounding. |

2.9 As shown in Chart 2.1, inflation has proved to be not only higher but more persistent than we and other forecasters anticipated. Starting in our October 2021 forecast, we have forecast a period of significantly above-target CPI inflation. In our four forecasts between October 2021 and March 2023, we have forecast peak quarterly CPI inflation of 4.4, 8.7, 11.1, and 10.7 per cent respectively, and to stay above the 2 per cent target for the following four to nine quarters. While our forecasts for peak inflation were typically above the consensus at the time, they typically assumed inflation would be less persistent than other forecasters. Box 2.1 explores in more detail why outturn inflation has so-far proved to be higher and more persistent than expected in our recent forecasts.

Chart 2.1: Successive OBR inflation forecasts

Box 2.1: Why has recent inflation been stronger than we forecast?

Over the past two years, inflation has turned out to be significantly higher than we and many other forecasters expected. This unexpected rise in inflation began in the second half of 2021 and was initially driven largely by post-pandemic strains in global supply chains that pushed up the price of tradable manufactured goods. Following the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, these pressures on goods prices were augmented by historic rises in energy and food prices (that were already increasing prior to the invasion). These externally-driven inflationary pressures have more recently been compounded by stronger domestically-generated inflation as the UK labour market has remained tight. Together, these factors pushed CPI inflation up to a peak of 11.1 per cent in October 2022, before declining to 6.7 per cent in August 2023 as external inflationary pressures receded.

The respective contributions of these external and domestic factors to stronger-than-expected inflation have also shifted over time. Our March 2021 inflation forecast was conditioned on gas prices that turned out to be five times higher than markets expected at the time we completed that forecast. But our March 2022 forecast was based on an assumption for energy prices that has turned out to be significantly closer to outturn. More of the explanation for our more recent underestimation of inflation can therefore be found in our assumptions for how the energy price shock propagated through to other prices in the rest of the economy.

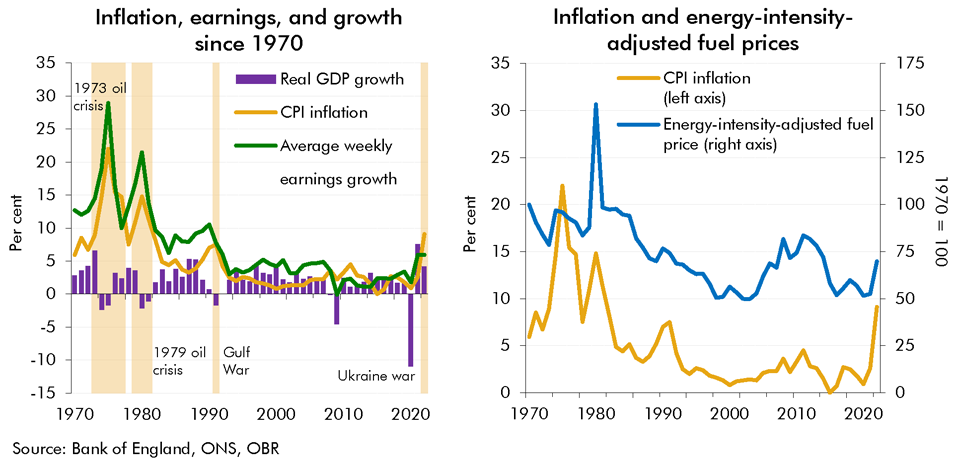

Informed by the impact of previous energy price shocks on the UK economy, our post-Russian-invasion forecasts for inflation assumed that higher energy prices would have a substantial knock-on a effect on wider prices in the economy. Previous spikes in global oil prices triggered by the 1973 Yom Kippur War and 1979 Iranian Revolution had significant and lasting effects on CPI inflation in the UK, as shown by the left-hand panel in Chart A. We discussed what lessons could be drawn from this period in Box 3.1 of our 2022 Fiscal risks and sustainability report. That analysis concluded that, while the knock-on effects from higher energy prices onto other prices in the economy were likely to be significant, the decline in the overall energy intensity of the UK economy (right-hand panel in Chart A) as well as changes to the structure of the labour market and the operation of monetary policy were likely to have muted those effects over the past half-century.

Chart A: Energy-intensity-adjusted fuel price and inflation, earnings, and GDP growth since 1970

In our March 2022 forecast, we assumed that these knock-on effects would add a further 25 per cent to the direct effect of higher energy prices on inflation. This assumption was based on a range of studies that suggested that, in general, the pass-through of modest rises in oil prices to wider, non-energy inflation had declined to near-zero, b but that larger energy price shocks still generated some wider pass-through to domestic prices. c To arrive at the 25 per cent assumption we therefore began by halving the size of the upper end of a range suggested by this external historical analysis (the upper end of the range of effectively assumed full and immediate pass-through of energy into other prices). As this analysis also generally incorporated shocks from previous decades, including the 1970s period, and countries outside of the UK, d we then further adjusted down the estimate based on our own analysis of the current weight of energy in production and consumption in the UK.

The subsequent evolution of CPI inflation suggests that our assumption for the size of these knock-on effects from higher energy prices has proved to be too low. Three factors are likely to form part of the explanation. First, there is growing evidence of strong non-linearities in the pass-through of energy shocks, with stronger pass-through when inflation is already high. e In this case, soaring gas prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine came on top of already rising prices of goods in the wake of the pandemic, compounding its inflationary effects. Second, the post-pandemic labour market has been tighter than expected which put labour in a stronger bargaining position in seeking to protect their real wages in the face of surging prices for energy, food, and other essentials. Finally, it is possible that increases in Bank Rate since 2022 have taken longer than we expected to reign in growth in aggregate demand, despite adjustments made for the growth in the number of fixed rate mortgages since monetary policy was last tightened significantly in the period preceding the global financial crisis.

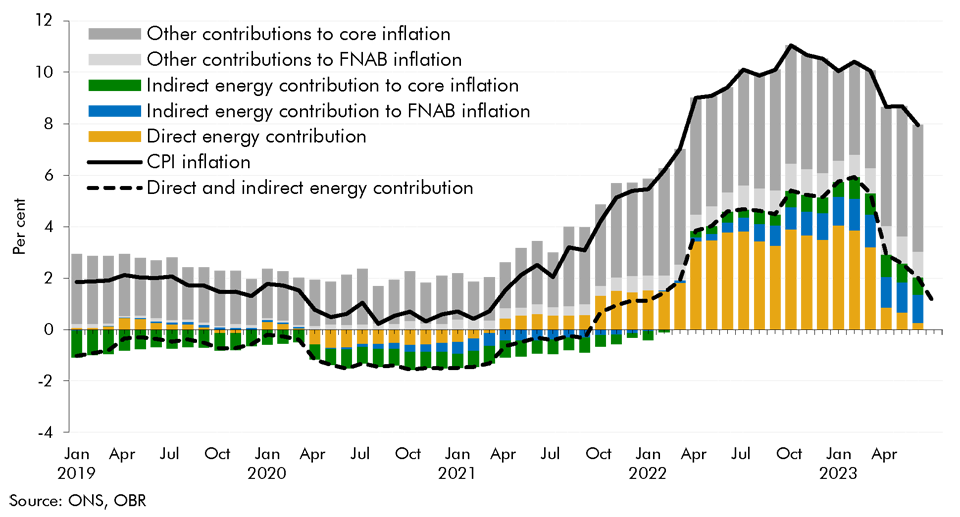

Our latest analysis supports the conclusion that elevated energy prices have had a larger overall impact on CPI inflation than we anticipated. To evaluate the size and timing of the knock-on effects of the 2022 energy shock, we decompose headline CPI inflation into: the direct energy contribution; the indirect contribution to core and to food and non-alcoholic beverages (FNAB) inflation; and other contributions to core and FNAB inflation (which will also include some of the wider knock-on effects from higher energy prices). f Chart B shows that the direct contribution (dark yellow column) peaked at 4.0 percentage points in January 2023 and averaged 3.6 percentage points over the 12 months to March 2023. The indirect energy effects (blue and green columns) started to make a positive contribution around mid-2022, peaked at 2.1 percentage points in March 2023 and averaged 1.6 percentage points over the twelve months to June 2023. This suggests the additional indirect effects of energy on CPI inflation have therefore been just under half the size of the direct energy impact over this period, or almost twice as large as our initial estimate.

Chart B: Contributions to CPI inflation

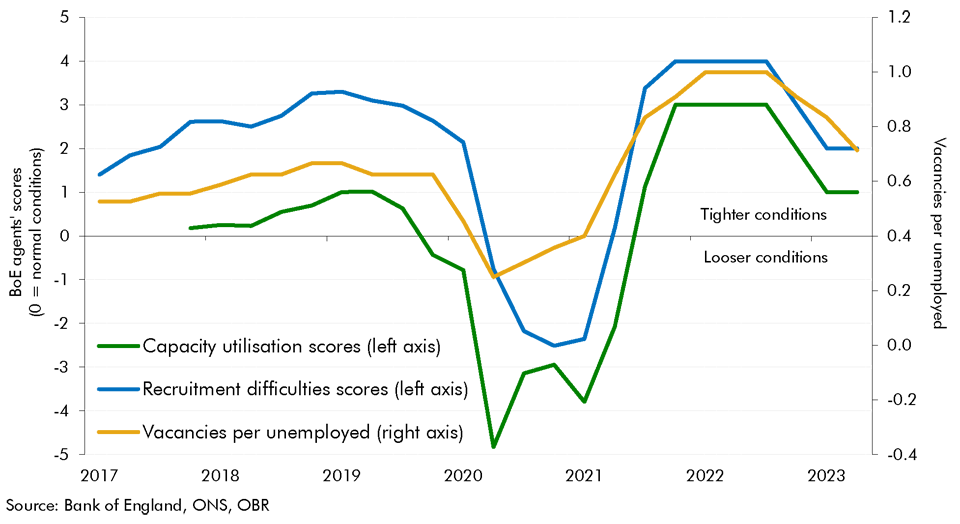

Some of the remaining unexpected strength of inflation is also likely to be explained by a greater degree of excess demand in the economy than we thought, resulting in greater domestically-generated inflation than anticipated. Survey measures of capacity utilisation and recruitment difficulties have been relatively high since the energy price shock (Chart C) g . While they have fallen back more recently, they are still in positive territory, indicating ongoing tightness in product and labour markets. The number of vacancies relative to the unemployed population shows a similar pattern of labour market tightness; it soared to record-highs of 1 vacancy per unemployed in mid-2022 and has since only fallen to 0.7, still well above its historical average of 0.4.

Chart C: Indicators of capacity utilisation and labour market tightness

In our upcoming Autumn 2023 forecast we will revisit this assessment of the inflationary impacts of the energy shock. We will also review the extent to which other macroeconomic factors such as tightness in labour and product markets; the evolution of the fiscal and monetary policy stances; inflation expectations; and lending and money supply growth might affect the evolution of inflation.

a) These effects include the indirect impact of raising the costs of producing other goods and services in proportion to the energy intensity of their production, as well as additional “second round” effects, including compensatory wage demands and the response of fiscal and monetary policy, as explained in Box 2.2 of our March 2022 EFO.

b) See Conflitti, C. and M. Luciani, Oil Price Pass-Through into Core Inflation, 2017; Millard, S., An estimated DSGE model of energy, costs and inflation in the UK, 2011; Choi, S., et al, Oil Prices and Inflation Dynamics: Evidence from Advanced and Developing Economies, 2017.

c) See Abdallah, C. and K. Kpodar, How Large and Persistent is the Response of Inflation to Changes in Retail Energy Prices?, June 2020.

d) See European Central Bank, Oil prices – their determinants and impact on euro area inflation and the macroeconomy, August 2010.

e) See De Santis, R. and Tornese, T. Energy supply shocks’ nonlinearities on output and prices, August 2023; Garzon, A. and Hierro, L., Asymmetries in the transmission of oil price shocks to inflation in the eurozone, December 2021.

f) We estimate a Vector Autoregressive Model (VAR) with monthly data from January 1989 to June 2023, and include energy inflation, food and non-alcoholic beverage inflation, core inflation (defined as all items excluding energy and food and non-alcoholic beverages) and control for the unemployment rate. We do not control for negotiated wage growth as average weekly earnings monthly data in the UK is only available from 2000. Our approach follows a similar methodology to Corsello, F. and Tagliabricci, A. Assessing the pass-through of energy prices to inflation in the euro area, February 2023 and Pallara, K., et al, The impact of energy shocks on core inflation in the US and the euro area, August 2023. Following the former study, we do not directly control for inflation expectations or monetary policy, though this impact should appear on the ‘other’ non-energy contributions in Chart B.

g) The Bank of England Agents’ scores are judgement-based assessments, based on conversations with businesses. Scores for recruitment difficulties and capacity utilisation reflect conditions relative to normal (0 indicates normal conditions, and +5 or -5 extreme ones).

Real GDP

2.10 Real GDP growth in 2022-23 was overestimated in the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts by 3.3 and 0.6 percentage points respectively, partly due to the supply shock stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The associated rise in energy prices increased the price of a major input into the production of goods and services in the UK. This, alongside global supply bottlenecks, weighed on productivity in the UK economy. With the UK being a net importer of energy and the other goods that were affected by supply bottlenecks, the rise in the price of these products eroded real wages, which in turn dragged on consumption growth. Labour market participation has also been weaker than we expected in 2021 mainly due to a stronger and more persistent increase in those who report being long term sick. The overestimate of GDP growth in 2022-23 in the March 2021 forecast also reflects our underestimation of the level of GDP in 2021-22 as the economy rebounded more quickly from the pandemic. [4]

2.11 Table 2.4 breaks down the real GDP growth forecast differences for 2022-23 into the expenditure components of GDP:

- Weaker consumption explains 3.9 percentage points of the difference between the March 2021 forecast and outturn, consistent with higher-than-expected inflation and interest rates following the invasion. The March 2022 forecast also overestimated consumption although by a much smaller margin, explaining 0.2 percentage points of the GDP growth forecast miss.

- Weaker business investment contributed 0.6 percentage points to the difference between the March 2021 forecast and the outturn. Business investment growth was revised down in March 2022, and subsequently was broadly in line with outturn, partly reflecting a reduced assessment of the impact of the super-deduction on investment.

- Net trade was less of a drag on growth than expected across both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, respectively contributing 1.0 and 1.5 percentage points more to GDP growth than forecast. This is partly due to stronger-than-expected export growth. However, changes in data collection mean UK trade data over recent years are even more prone to revision than usual. [5] Adjusted trade figures published by the Bank of England, stripping out the impact of trade measurement issues, point to lower imports than indicated by the latest ONS outturns. [6]

- Other components contributed less to GDP growth than anticipated in the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, explaining 0.4 and 1.3 percentage points of the respective misses. This is partly owing to changes in inventories, as firms built up fewer stocks than expected, likely owing to supply disruptions. Other components of GDP are also highly volatile and subject to large revisions.

Table 2.4 Expenditure contributions to real GDP growth in 2022-23

| Percentage points | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private consumption | Business investment | Private residential investment | Total government | Net trade | Other | GDP | |

| March 2021 forecast | 5.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -1.8 | 5.0 |

| March 2022 forecast | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -0.5 | -0.1 | 2.2 |

| Latest data | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | -0.3 | 0.9 | -1.4 | 1.6 |

| Difference (1) | |||||||

| March 2021 | -3.9 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -0.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | -3.3 |

| March 2022 | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.2 | -0.6 | 1.5 | -1.3 | -0.6 |

| 1) Difference in unrounded numbers. |

2.12 Chart 2.2 shows how these differences in growth rates affected the performance of our forecasts for the levels of real GDP in 2022-23 in our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. In both forecasts, more pessimistic growth trajectories meant our forecast undershot the latest outturn. But these comparisons are complicated by revisions to the historical level of GDP: since our March 2022 forecast, the level of GDP in the 2022-23 fiscal year has been heavily affected by an ONS downgrade to the extent of the recovery in GDP following its 2020-21 trough. [7]

It also highlights that in our most recent March 2023 forecast, the near-term economic downturn was forecast to be shorter and shallower than projected in November 2022, partly due to a lower interest rate path and a faster-than-anticipated fallback in European gas prices.

Chart 2.2: Successive forecasts for the level of real GDP

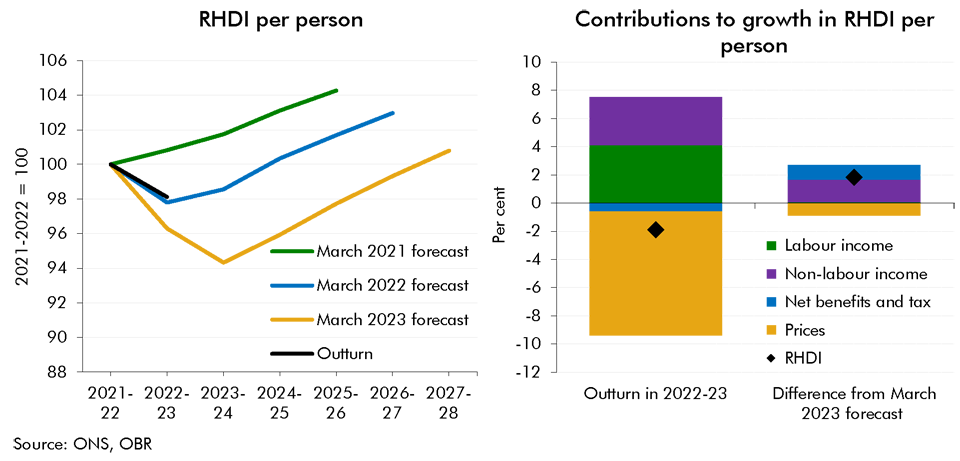

Box 2.2: Why has real household disposable income been stronger than forecast

Following the invasion, we projected that in 2022-23 rising inflation would lead to the biggest fall in real household disposable income per person, a measure of living standards, in any single financial year since ONS records began in 1956-57. The March 2022 EFO forecast RHDI per person to fall by 2.2 per cent in 2022-23, and to return sustainably to its pre-pandemic level only in 2024-25. More recently, in March 2023 we expected this fall to be substantially larger at 3.7 per cent, followed by another fall in 2023-24 of 2.0 per cent.

ONS outturn estimates from June 2023 suggest that RHDI per capita fell by 1.9 per cent in 2022-23, still constituting the largest single-year fall on ONS records, but 1.8 percentage points less than we forecast in March 2023 (although broadly in line with the March 2022 forecast). It is possible that future data releases lead to further revisions, given measurement challenges and uncertainties around 2022-23 incomes data.

The difference in outturns relative to the March 2023 forecast is largely explained by net benefits and taxes having supported RHDI more than expected, and non-labour income turning out stronger than forecast. Specifically, net benefits and taxes contributed 1.0 percentage points more to growth in RHDI 2022-23 relative to the previous financial year (subtracting 0.6, rather than 1.6 percentage points). Non-labour income growth added 1.6 percentage points more than forecast in March 2023 (adding 3.4 percentage points altogether). Growth in labour incomes were broadly in line with outturns, only contributing 0.1 percentage points more than previously expected (4.1 percentage points in total). Stronger than expected inflation dragged on RHDI growth by 0.9 percentage points more than we forecast in March (taking 8.8 percentage points off growth).

Chart D: RHDI per person

The strength in net benefits and taxes is largely explained by lower-than-expected June Quarterly National Account (QNA) outturns in household taxes on income and wealth as well as employee social contributions. Public sector finances data on receipts suggests higher outturns for taxes and contributions, so there is a possibility the ONS revises 2022-23 figures in its upcoming September QNA release.

Within non-labour incomes, higher interest rates have provided a bigger boost to RHDI in 2022 23 than we expected in March 2023, though over time we expect there to be little impact from interest rates on aggregate RHDI.

As market interest rates increase, mortgage and other interest payments rise, but higher interest rates also lift interest income on household savings. Given the stock of overall household deposits is roughly equal to the stock of debt, the impacts of these changes broadly offset in aggregate, although timings can differ. In 2022-23, the effect from interest income dominated as rising deposit rates affected all households with interest-bearing savings, while the rise in the number of fixed mortgage contracts meant that only a fraction of those with mortgage debt moved to higher rates in that year. Overall household investment income was £8.9 billion more than our March 2023 forecast expected (0.5 per cent of household disposable income), while overall interest payments were £0.6 billion higher.

As consumption came in closer to our March 2023 forecast, underestimating RHDI relative to the June data release led us to underestimate household savings. All else equal, stronger-than-expected household incomes enable households to consume more, which provides support to wider economic activity. But it can also lead to higher household savings. While outturns for consumption in 2022-23 have been broadly in line with our March 2023 forecast, the household saving ratio (excluding net pension adjustments) has turned out to be 1.5 percentage points higher than we expected.

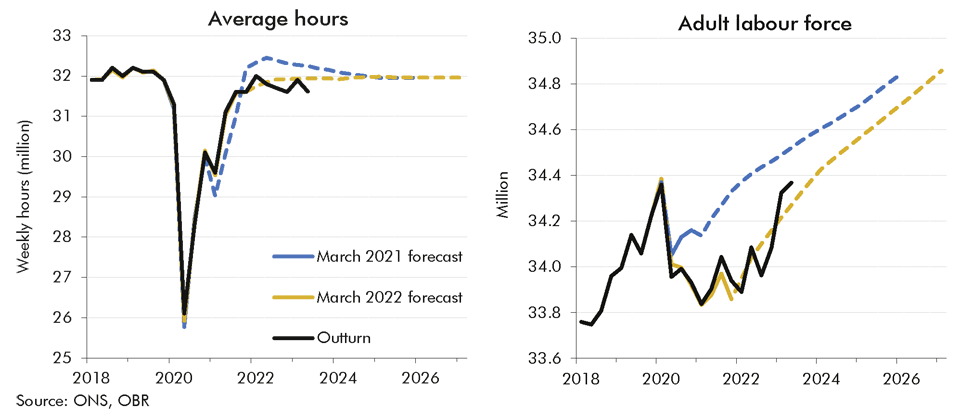

Labour market and productivity

2.13 Labour supply growth in 2022-23, measured in terms of total hours worked, was 2.2 and 0.6 percentage points less than estimated in both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. This undershoot mainly reflects a significant overestimation of average hours worked, which did not recover to pre-pandemic levels as swiftly as had been expected following the closure of the furlough scheme (as shown in the left panel of Chart 2.3). The larger rise in part-time employment of around 340,000 over the year to the first quarter of 2023, compared with only 20,000 in full-time employment, may have weighed on overall average hours worked.

2.14 The labour force, which had undershot expectations significantly during 2021-22, began to recover at a pace more in line with our forecasts over 2022-23 (as shown in the right panel of Chart 2.3). This was led by a recovery in activity rates, especially among students and those with caring responsibilities, potentially motivated by the sharp rise in the cost of living. This more than offset a continued rise in those unable to work due to long term sickness, which reached record levels of more than 2.5 million by September 2022. So, while the level of the labour force was lower than had been expected in the March 2021 forecast, the error in the 2022-23 growth rate was only 0.1 percentage points below the outturn. The March 2022 forecast error was 0.1 percentage points above the outturn.

Chart 2.3: Average hours and adult labour force

2.15 Labour market conditions proved tighter than expected as the closure of the furlough scheme did not result in a rise in the unemployment rate over the second half of 2021-22 as expected in the March 2021 forecasts. Also, the robust recovery in employment over 2022-23 overshot expectations, with the number of vacancies reaching record levels both in absolute terms, relative to new hires, and to those either unemployed or inactive. The outturn for annual employment growth in 2022-23 was 0.3 and 0.1 percentage points higher than expected in the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. This resulted in the unemployment rate falling faster than expected, undershooting both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts by 2.0 and 0.3 percentage points respectively.

2.16 The assessment of our forecast performance relative to outturn has been complicated by measurement issues with the ONS’ Labour Force Survey (LFS) which is the main source of our estimates. Comparisons to other datasets such as the HMRC’s PAYE based employees and the ONS’ Workforce Jobs Survey suggest the LFS may be underestimating employment, as while it shows a rise in employment of 360,000 in the year to the first quarter of 2023, the Workforce Jobs Survey indicates the rise is closer to 1 million. The HMRC dataset, which only covers employees, shows a rise of close to half a million. Some of the difference may be explained by differences in content, coverage and methodology between the datasets. [8]

2.17 Nominal average earnings growth was stronger than expected by our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, by 3.3 and 0.7 percentage points respectively. The difference was due to labour market conditions proving much tighter than anticipated, alongside markedly higher inflation. As mentioned above, a rapid pick-up in labour demand led to a tightening in labour markets. This was initially driven by private sector pay growth, which rose strongly as employers increasingly struggled with recruitment and retention against a backdrop of strong churn, record vacancies and rising inflation. More recently, public sector earnings growth has caught up, boosted by one-off lump sum payments from backdated pay increases and bonus payments. Strike action has also contributed to the upward pressure.

2.18 Productivity growth was 1.2 percentage points weaker than expected in the March 2021 forecast, which overestimated GDP growth by 3.3 percentage points in 2022-23 but total hours growth by only 2.2 percentage points. Both were revised lower in the March 2022 forecast, which predicted no growth in productivity, and ended up much closer to the 0.1 per cent outturn. The weakness in productivity growth over the year suggests that the post-pandemic rebound in total factor productivity may not have been as strong as expected.

Table 2.5 Labour market in 2022-23

| Total hours (million) | Average hours (hours) | Total employment (thousand) | Labour force (thousand) | Unemployment rate | Average earnings | Productivity per hour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent change | |||||||

| March 2021 forecast | 3.7 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | -0.2 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| March 2022 forecast | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | -0.2 | 5.1 | 0.0 |

| Latest data | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 | -0.4 | 5.8 | 0.1 |

| Difference (1) | |||||||

| March 2021 | -2.2 | -2.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 3.3 | -1.2 |

| March 2022 | -0.6 | -0.8 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Levels change | |||||||

| March 2021 forecast | 38 | 1 | 208 | 153 | -55 | ||

| March 2022 forecast | 22 | 0 | 266 | 215 | -51 | ||

| Latest data | 16 | 0 | 311 | 170 | -142 | ||

| Difference (1) | |||||||

| March 2021 | -22 | -1 | 103 | 17 | -87 | ||

| March 2022 | -6 | 0 | 45 | -46 | -91 | ||

| 1) Difference in unrounded numbers. |

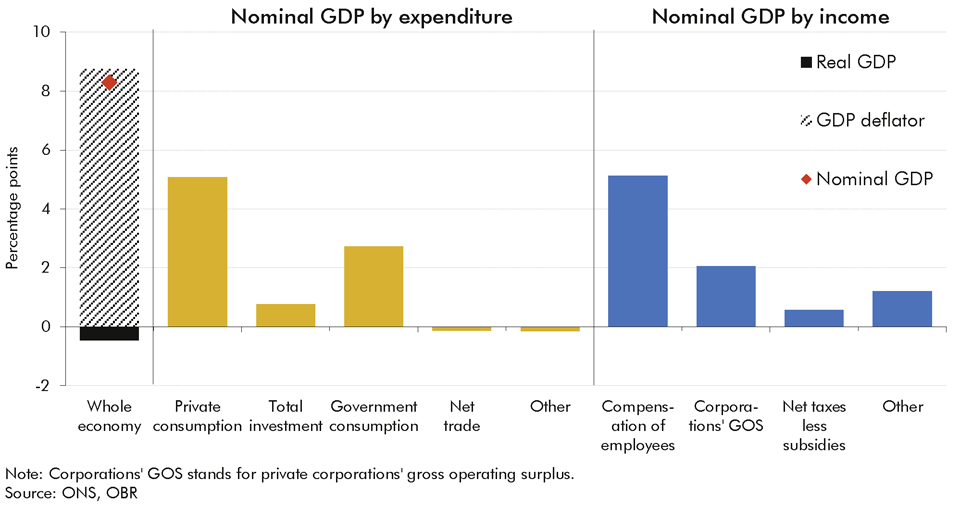

Nominal GDP

2.19 Our economy forecast provides the basis for the fiscal forecasts that we use to assess the Government’s performance against its fiscal targets. The most fiscally important elements of the economy forecast are those that drive the major tax bases, namely the income and expenditure components of nominal rather than real GDP. These are influenced by both real GDP and whole economy inflation, as well as by changes in the share of whole economy nominal GDP accounted for by each component. As a result, the fiscal forecast differences discussed in Chapter 3 tend to be influenced heavily by surprises in the composition of nominal GDP as well as its overall size. These influences were important to consider in 2022-23: a year in which unexpectedly high inflation lifted certain expenditure components of GDP, as well as nominal earnings. In this section, we briefly review the key nominal forecasts that underpin the analysis of fiscal forecast differences in 2022-23 that is presented in Chapter 3.

March 2021 forecast

2.20 Stronger-than-expected growth in the GDP deflator meant our March 2021 forecast underestimated cumulative growth in nominal GDP from 2020-21 to 2022-23, despite cumulative real GDP growth turning out weaker than expected. [9] The GDP deflator was forecast to decline by 2 per cent over this period, but the unexpected rise in energy prices and the costs of supply chain disruptions led to 6.8 per cent growth. As a result, nominal GDP increased by 21.3 per cent over 2020-21 to 2022-23, 8.3 percentage points more than we forecast, though real GDP growth was weaker by 0.5 percentage points. On the expenditure side, this is reflected in nominal consumption contributing 5.1 per cent more to nominal GDP than forecast in March 2021. The growth contributions of nominal investment and government consumption were 0.8 percentage points and 2.7 percentage points higher than expected, while net trade made a contribution in line with our expectations at the time.

2.21 On the income side, there was a large upward surprise in the contribution of employees’ compensation, adding 5.1 percentage points more to cumulative nominal GDP growth between 2020-21 and 2022-23 than forecast. The gross operating surplus (GOS) of corporations also grew more strongly than expected, partly due to additional profits made by energy companies and the impact of energy support policies on the rest of the corporate sector, adding an additional 2 percentage points to nominal GDP growth. Given large alignment adjustments in recent data releases, there is still some uncertainty about 2022-23 outturns.

Chart 2.4: March 2021 forecast differences in contributions to cumulative nominal GDP growth between 2020-21 and 2022-23

March 2022 forecast

2.22 Faster-than-expected whole economy inflation meant our March 2022 forecast for nominal GDP growth in 2022-23 was also lower than what eventually happened. [10] While real GDP again grew by less than expected (by 0.6 percentage points), nominal GDP growth exceeded expectations by 1.9 percentage points. On the expenditure side, this was again spread across surprises to nominal consumption, investment, government consumption and net trade, which added 1.3 percentage points, 0.3 percentage points, 0.1 percentage points and 1.1 percentage points more to nominal GDP growth, respectively. Driven by real factors, other components provided a drag on nominal GDP growth, lowering nominal GDP by 1 per cent in 2022-23, rather than by 0.1 per cent that was expected in March 2022 (although as noted above these elements are highly volatile and subject to large revisions).

2.23 On the income side, our March 2022 forecast only slightly underpredicted the growth contribution of employees’ compensation, as slightly weaker-than-expected hours growth was offset by slightly stronger-than-expected growth in average earnings. The contribution of corporations’ GOS was more significantly underestimated by 2.4 percentage points in our March 2022 forecast. This was partly offset by a 1.1 percentage point smaller-than-expected contribution of net taxes less subsidies. These differences reflect uncertainty about the impact of energy support schemes and adjustments made by the ONS to align the different measures of GDP. As a result, it is possible that outturns for 2022-23 will be revised in future data releases.

Chart 2.5: March 2022 forecast differences in contributions to cumulative nominal GDP growth in 2022-23

Chapter 3: The public finances

Introduction

3.1 This chapter assesses the performance of our March 2021 fiscal forecast and our March 2022 fiscal forecast for the 2022-23 financial year. In each case we explore the differences between our forecast and the latest outturn data for:

- public sector net borrowing (PSNB), beginning with a summary of how our estimates of PSNB in 2022-23 evolved over successive forecasts, and how these compared to estimates produced by other forecasters;

- the receipts and spending forecasts that underpin our March 2021 and March 2022 PSNB forecasts for 2022-23; and

- our March 2021 and March 2022 public sector net debt (PSND) forecasts for 2022-23.

3.2 Differences between outturn data and our forecasts have been broken down into:

- policy changes – differences due to policies announced after the publication of the forecast;

- economic factors – differences due to the changes in underlying economic conditions relative to our initial forecast;

- classification changes – differences due to items being reclassified into or out of the public sector following the forecast; and

- fiscal forecasting differences – any remaining differences that cannot be explained by the other categories, such as those related to how well the underlying forecast model matches reality or judgements that we impose on top of the effects of economic determinants.

The evolution of our borrowing forecast for 2022-23

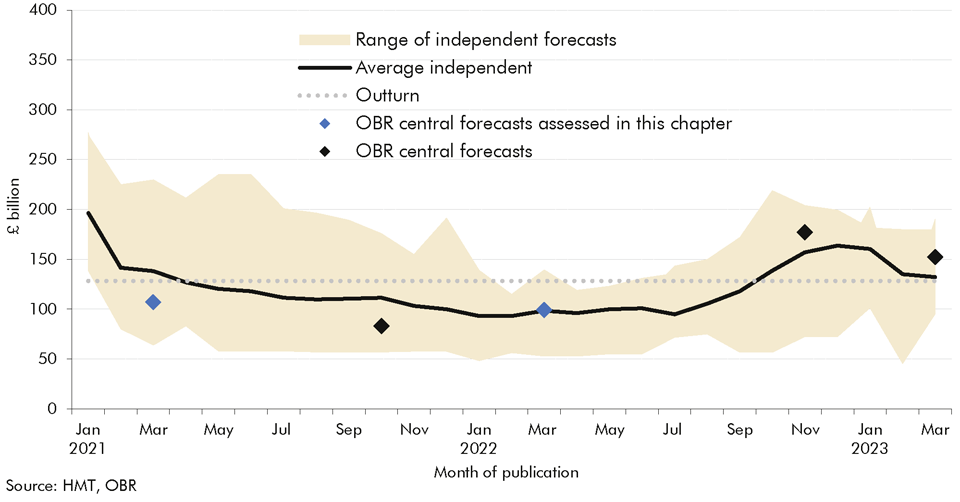

3.3 PSNB rose by 4.5 per cent in cash terms from £122.9 billion (5.3 per cent of GDP) in 2021-22 to £128.4 billion (5.1 per cent of GDP) in 2022-23. Outturn PSNB overshot our March 2021 forecast by £21.5 billion (0.8 per cent of GDP), our October 2021 forecast by £45.4 billion (1.8 per cent of GDP), and our March 2022 forecast by £29.3 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP).

3.4 However, our November 2022 forecast of £177 billion (7.1 per cent of GDP), produced in the wake of the Ukraine war, the ensuing energy crisis, rising global interest rates, and policy measures announced over the Autumn, ended up overestimating outturn by £48.6 billion (1.9 per cent of GDP). This was due in large part to the ensuing fall in energy prices and interest rates which reduced expenditure on energy support schemes and debt interest respectively. Our most recent estimate of borrowing in March 2023 was £152.4 billion (6.1 per cent of GDP) – which was £23.9 billion (0.9 per cent of GDP) above outturn. Lower borrowing mainly reflects lower central government spending and differences in estimates for funded pensions.

3.5 Chart 3.1 below shows how each of these forecasts compared to outturn as well as the average and range of independent forecasts published contemporaneously. Our forecasts in March 2021 and October 2021 were relatively more optimistic than the average forecast, while our March 2022 forecast was in line with the average. During the summer of 2022, borrowing forecasts became more pessimistic reflecting the unfolding economic landscape – the steep rise in energy costs, rising inflation, and the fallout from the mini-Budget – with OBR’s November 2022 and March 2023 more pessimistic than average. The remainder of this chapter focuses on the performance of our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts and the reasons they differed from outturn.

Chart 3.1: Range of forecasts for 2022-23 PSNB

3.6 A breakdown of these PSNB forecast differences into spending and receipts are presented in Table 3.1. Against both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, higher-than-expected receipts were more than offset by higher-than-expected spending, resulting in higher borrowing by end of the financial year.

3.7 Against our March 2021 forecast, borrowing came in £21.5 billion higher than expected. Of this overall difference:

- Economic factors are neutral due to very large differences on receipts and spending almost exactly offsetting: £88.0 billion in higher tax receipts offset by higher spending of £88.1 billion. Both effects are in large part due to higher-than-anticipated inflation:

- higher inflation and interest rates led to an additional £87.0 billion in inflation-linked and nominal debt interest. Welfare spending was only £1.8 billion higher than expected, as the positive effect of higher inflation and earnings on uprating (£4.8 billion) was offset by the effect of lower unemployment on universal credit spending (£3.7 billion).

- higher inflation also increased the key nominal tax bases. In the two years following the March 2021 forecast, wages and salaries rose at more than double the rate anticipated, consumption grew by 6.3 percentage points faster than forecast, and profits by 3.2 percentage points faster than forecast, contributing along with other economic factors to £88.0 billion higher receipts than forecast.

- Policy changes drove up borrowing by £78.9 billion due primarily to the Energy Price Guarantee and other support provided to help households and businesses to cope with the sudden rise in the cost of energy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See Box 3.1 for full details of the costs of these policies.

- Other factors reduced borrowing, partially offsetting the previously described differences by £57.4 billion: a £46.3 billion underestimate of receipts, and a £11.1 billion overestimate in spending. [11] Of the £46.3 billion overshoot in receipts unexplained by policy or economic determinants, around 37 per cent (£17.2 billion) was onshore corporation tax where the effective tax rate was higher than anticipated, and around 27 per cent (£12.3 billion) was income tax and National insurance contributions (NICs).

Chart 3.2: March 2021 PSNB error for 2022-23 by source

3.8 Our March 2022 forecast also underestimated borrowing by £29.3 billion. Of this overall difference:

- Forecast differences due to economic assumptions make up £5.7 billion of the overall PSNB error. £27.9 billion of the difference was due to higher spending – mainly from the underestimate of the inflation uplift acting on index-linked government debt and Bank rate on payments made from the Asset Purchase Facility (APF). This was partly offset by £22.2 billion of underestimated receipts from faster growth in tax bases and lower welfare spending (£0.6 billion).

- Policy changes make up £52.1 billion of total PSNB error. £47.1 billion (90 per cent) was due to new spending policies – particularly on energy support schemes (see Box 3.1) and cost-of-living payments (£8.4 billion). £4.9 billion was due in part to the cancellation of NICs rate rise after 7 months.

- Other factors reduced borrowing by £28.5 billion: £10.3 billion lower spending than anticipated and £18.2 billion higher receipts. [12] The unexplained receipts overshoot was mostly in onshore corporation tax where the effective tax rate has been much stronger than anticipated in March 2022’s forecast.

Chart 3.3: March 2022 PSNB error for 2022-23 by source

Table 3.1: 2022-23 receipts, spending and net borrowing forecasts

| £ billion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forecast | Outturn | Difference | of which: | ||||

| Classification changes | Policy changes | Economic factors | Fiscal forecasting difference | ||||

| Borrowing (PSNB) | |||||||

| March 2021 | 106.9 | 128.4 | 21.5 | 0.0 | 78.9 | 0.1 | -57.4 |

| March 2022 | 99.1 | 128.4 | 29.3 | 0.0 | 52.1 | 5.7 | -28.5 |

| Receipts (PSCR) | |||||||

| March 2021 | 885.4 | 1,023 | 137.5 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 88.0 | 44.9 |

| March 2022 | 987.5 | 1,023 | 35.5 | 0.7 | -4.9 | 22.2 | 17.5 |

| Spending (TME) | |||||||

| March 2021 | 992.3 | 1,151 | 159.1 | 1.4 | 82.1 | 88.1 | -12.5 |

| March 2022 | 1,087 | 1,151 | 64.8 | 0.7 | 47.1 | 27.9 | -11.0 |

| Note: In spending economic factors, we have included debt interest and a ready-reckoned estimate of the impact of changes in economic determinants on welfare spending. |

Receipts

3.9 Receipts increased as a share of GDP rise from 39.4 per cent in 2021-22 to 40.4 per cent in 2022-23. Receipts were stronger than anticipated in both the March 2021 EFO (by £137.5 billion) and the March 2022 EFO (by £35.5 billion). Key drivers include:

- Economic determinants which make up £88.0 billion (64 per cent) of the March 2021 forecast difference and £22.2 billion (63 per cent) of the March 2022 forecast difference. This was driven by higher wages and salaries, profits, and nominal consumer spending than anticipated in either forecast. The March 2021 EFO forecast for earnings growth over 2021-22 and 2022-23 was 5 per cent compared to outturn of 13.0 per cent. Non-oil, non-financial profits were stronger than assumed in both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts despite higher wage and energy costs.

- Policy changes make up £3.2 billion (2 per cent) of the March 2021 forecast difference, and lowered receipts by £4.9 billion relative to the March 2022 forecast. Policies brought in since the March 2021 EFO include the usual fuel duty freeze £1.5 billion and the temporary 5p reduction in main rates of petrol and diesel £2.4 billion, business rates changes, the 1¼ percentage points rise in dividend taxation, and the rise in the primary NICs threshold from July 2022. After the March 2022 EFO, the energy profits levy was introduced in May 2022, and the temporary 1¼ percentage points rise in employee, self-employed and employer NICs was cancelled in the September 2022 mini-budget.

- Fiscal forecast difference makes up £46.3 billion (34 per cent) of the March 2021 forecast difference and £18.2 billion (51 per cent) of the March 2022 forecast difference. Companies in relatively tax-rich sectors continued to do well in 2022-23, and large companies saw higher profits than expected. There was a sharp rise in net interest margins boosting financial sector corporation tax; and greater than expected dividend income forestalling to avoid the 1¼ percentage point rise in dividend income tax which came into effect in April 2022.

Income tax and NICs

3.10 PAYE IT in 2022-23 grew 10 per cent on 2021-22 figures to £212.0 billion, overshooting our March 2021 forecast by £30.3 billion (17 per cent) and our March 2022 forecast by £3.1 billion (1 per cent).

3.11 Self-assessed income tax (SA IT) grew by 16 per cent on 2021-22 figures, reaching £42.9 billion in 2022-23; overshooting March 2021 estimates by £12.6 billion (42 per cent) and March 2022 estimates by £3.4 billion (9 per cent).

3.12 National insurance contributions (NICs) exceeded our March 2021 forecast by £24.3 billion (16 per cent) but undershot our March 2022 forecast by £2.1 billion (around 1 per cent).

3.13 The drivers of difference in each of these personal tax receipts forecasts are broadly similar:

- Economic determinant differences (primarily higher wages and salaries) made up £47.3 billion (72 per cent) of the March 2021 forecast difference and £7.2 billion of the March 2022 forecast difference. For PAYE, higher average wages and, to a lesser extent, higher numbers of employees than anticipated drove the overshoots. For self-assessed income tax, March 2021’s difference was driven by higher self-employment income, while for March 2022, it was higher dividend income than forecast – in large part likely due to forestalling ahead of the 1¼ percentage points rise in dividend tax rates from April 2022. It remains difficult to estimate the self-assessment tax base using existing data: tax returns data for 2021-22 liabilities shows faster growth rates in self-employment income and self-employed numbers than captured in the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and National Accounts. [13]

- Policy changes due to the increase in NICs and dividend tax rates following March 2021’s forecast, and a reversal of parts of these policies following March 2022’s forecast. For the March 2021 forecast, £6.1 billion (9 per cent) of the error can be explained by policy changes including the temporary rise in NICs from April 2022, alongside the 1¼ percentage points rise in dividend tax rates. These were tempered by the increase in the NICs primary threshold from July 2022. Policy changes after March 2022 lowered receipts by £6.4 billion mainly due to the cancellation of the NICs rate rise from November 2022 which lowered receipts by £7.1 billion.

- The remaining fiscal forecasting residual captures differences in modelling as well as in-year receipts estimates. For March 2021’s forecast, the residual fiscal forecasting difference made up £12.3 billion of the total error. For March 2022, fiscal forecasting differences were £1.8 billion. In both cases these differences are largely due to in-year receipts estimates being set too low.

VAT

3.14 VAT receipts in 2022-23 grew by £18.8 billion (13.1 per cent) to £162.1 billion. This exceeded our March 2021 forecast by £16.5 billion (11.3 per cent) and our March 2022 forecast by £7.9 billion (5.1 per cent).

- Of the £16.5 billion overshoot against the March 2021 forecast, economic factors account for £13.7 billion, mainly due to higher inflation resulting in stronger nominal consumer spending (£7.0 billion) and higher central government procurement (£4.0 billion). The fiscal forecast error of £2.0 billion reflected higher deductions offset by higher spending on standard rated goods and other fiscal modelling factors. The remaining £0.8 billion is due to subsequent policy announcements increasing VAT receipts.

- Of the £7.9 billion overshoot against the March 2022 forecast, economic factors account for £6.3 billion driven by higher housing investment (£2.6 billion) and higher nominal consumer spending due to higher inflation (£2.4 billion). The fiscal forecast error of £1.5 billion largely reflects the timing of receipts at the start and end of the financial year (£1.8 billion). Subsequent policy announcements increased VAT receipts by £0.1 billion.

Onshore corporation tax

3.15 Onshore corporation tax receipts have consistently come in higher than expected through the pandemic and more recently. Outturn receipts of £72.5 billion in 2022-23 were £24.3 billion (50.5 per cent) and £15.6 billion (27.5 per cent) higher than the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively.

- Of the £24.3 billion overshoot against the March 2021 forecast, around three-quarters comes from higher payments of tax by non-oil, non-financial companies and the rest from financial sector companies. Cumulative profit growth of non-oil, non-financial companies was just over 3 percentage points higher than assumed in the March 2021 forecast, while financial company profits are estimated to have risen by 50 per cent rather than the 13 per cent assumed in the March 2021 forecast. These stronger economic determinants explain £7.7 billion of the overshoot with much of the rest due to fiscal forecasting differences. This is likely to be due to a combination of the starting point for the forecast (e.g. the outturn for the previous year) proving too low and a stronger pre-measures effective tax rate.

- The £15.6 billion overshoot in receipts relative to the March 2022 forecast were from both non-oil, non-financial companies (£14.2 billion) and from financial companies (£4.3 billion). Profit growth of non-oil, non-financial companies rose by 7.3 per cent in 2022 against a forecast fall of 1.4 per cent. Profits rose despite higher wage and energy costs (possibly partly helped by the government energy schemes). Financial company profits were also 11 per cent higher than we assumed in the March 2022 forecast. This explained £6.8 billion of the overshoot with the rest explained by fiscal forecasting differences. As with the March 2021 forecast, a combination of a too low starting point and a higher-than-expected effective tax rate are likely to be the key drivers.

3.16 The starting point for our March forecasts will be heavily influenced by the latest estimate for receipts for the previous year. With most corporation tax paid with a lag, cash receipts in 2021-22 and 2022-23 will often relate to profits in the previous year (and accrue back to that year). These consistently surprised on the upside. The latest accrued corporation tax outturns for both 2021-22 and 2022-23 are over £8 billion higher than the estimates used for the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. In addition, ONS data on non-oil, non-financial profits has generally been revised up from the vintages used when making these forecasts.

3.17 A higher-than-expected effective tax rate is likely to be partly due to the strength of receipts being concentrated in a few relatively tax-rich sectors of the economy and among very large companies. Chart 3.3 in the January 2023 Forecast evaluation report shows the variation in the effective tax rate between sectors with the financial sector, professional services and retail all having a relatively high effective tax rate on their profits. Profits and the effective tax rate on those profits in the financial sector in 2022-23 benefited from the rise in net interest margins of retail banks. We also assumed in these forecasts that not all of the unexplained strength (over and above that explained by economic determinants and other factors) would push through to future years. It looks like this proved to be a too pessimistic assumption.

Other receipts

3.18 Fuel duties in 2022-23 were £25.1 billion. This fell short of our March 2021 forecast by £4.1 billion largely due to policy changes announced in Spring Statement 2022 including the duty freeze costing £1.5 billion and the temporary 5p reduction in main rates of petrol and diesel costing £2.4 billion. Compared to our March 2022 forecast, receipts were £1.1 billion lower, of which £0.3 billion is explained by economic factors and a further £0.2 billion is explained by an in-year forecast error for 2021-22. The remaining fiscal error of £0.5 billion is due to higher-than-expected petrol and diesel prices (£0.2 billion) and other fiscal modelling factors.

3.19 Air passenger duty (APD) in 2022-23 was £3.3 billion. This was £1.2 billion and £0.4 billion above our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. This reflects a stronger post-Covid recovery in air travel than anticipated.

3.20 Tobacco duty receipts in 2022-23 were £9.4 billion. This was £0.1 billion and £1.6 billion below our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. £0.6 billion of our March 2022 error is due to the timing of receipts around the start and the end of the financial year, and the rest is explained by tobacco receipts falling from their peaks quicker than expected after the pandemic.

3.21 Customs duty receipts were £5.4 billion in 2022-23. This was £2.3 billion above our March 2021 forecast. This is due to lower-than-expected utilisation of the preferential treatment on offer under the free-trade agreement with the EU and higher-than-expected electric vehicle imports from outside the EU, as explained in Box 3.1 of our January 2023 Forecast evaluation report. We have since updated our assumptions resulting in a smaller underestimate of £49 million (0.9 per cent) against our March 2022 forecast.

3.22 The UK emission trading scheme (ETS) receipts were £5.8 billion in 2022-23. This was £4.6 billion above our March 2021 forecast and only £36 million above our March 2022 forecasts, respectively. Of the March 2021 error, higher-than-anticipated carbon price explains £4.0 billion and the remaining error is explained by higher-than-expected numbers of allowances.

3.23 Capital gains tax receipts in 2022-23 were £16.9 billion. This was £6.2 billion and £2.0 billion higher compared to our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. Both surpluses are almost entirely explained by fiscal forecasting differences, reflecting the small number of high-value financial asset disposals in 2021-22 (like SA income tax, CGT receipts largely relate to liabilities in the previous financial year).

3.24 Inheritance tax receipts in 2022-23 were £7.1 billion. This was £1.3 billion and £0.4 billion higher compared to our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts respectively. The surplus from March 2021 is partly explained by stronger than expected growth in house prices and cash deposits. The March 2022 forecast difference is largely due to a fiscal forecast difference, reflecting higher deaths than forecast and a small number of large payments.

3.25 Stamp duty land tax receipts in 2022-23 were £15.4 billion. This was £2.0 billion above our March 2021 forecast but £0.4 billion below our March 2022 forecast. The March 2021 forecast difference is largely related to stronger growth in the housing market than expected, while the March 2022 forecast difference is more than explained by the September policy measure to increase the nil-rate band thresholds. For both forecasts, there is a positive fiscal forecast difference which may reflect a greater number of high value property transactions than assumed in the model.

3.26 UK oil and gas receipts (including offshore corporation tax, petroleum revenue tax and the energy profits levy) reached £9.5 billion in 2022-23. This was £9.1 billion higher than March 2021’s forecast, and £1.7 billion higher than our March 2022 forecast. For both the March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts, the Energy profits levy (EPL) introduced in May 2022 brought in £3.9 billion of unanticipated receipts. The remaining difference for the March 2021 forecast is due to much higher oil and gas prices. For March 2022, the EPL receipts surprise was partially offset by offshore corporation tax receipts coming in lower than expected by £2.2 billion (28 per cent). Lower receipts were driven by underlying fiscal forecast errors potentially including that the gas prices achieved by firms have been lower than the market prices assumed because of hedging and forward sales.

3.27 Business rates in 2022-23 were £28.3 billion. This was £3.3 billion and £1.2 billion lower than our March 2021 forecast and March 2022 forecast respectively. The 2021 Autumn Budget announcements to freeze the business rates multiplier for 2022-23 and provide relief for some retail, hospitality and leisure businesses explain around £2.5 billion of the March 2021 forecast difference.

3.28 Interest and dividend receipts in 2022-23 were £31.1 billion. This was £4.7 billion above our March 2021 forecast and £0.2 billion lower than our March 2022 forecast. Higher than expected interest rates have pushed up the return on the government’s financial assets such as bank deposits and foreign exchange reserves. This explained £3.7 billion of the difference in March 2021 and £1.1 billion of the difference in March 2022.

Table 3.2: Breakdown of March 2021 receipts forecast differences for 2022-23

| £ billion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forecast | Outturn | Difference, of which: | |||||

| Total | Classification changes | Policy changes | Economic factors | Fiscal forecast difference | |||

| Income tax and NICs | 361.3 | 427.0 | 65.7 | 0.0 | 6.1 | 47.3 | 12.3 |

| Value added tax (VAT) | 145.6 | 162.1 | 16.5 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 13.7 | 2.0 |

| Onshore corporation tax | 48.1 | 72.5 | 24.3 | 0.0 | -0.6 | 7.7 | 17.2 |

| Fuel duties | 29.2 | 25.1 | -4.1 | 0.0 | -3.9 | 1.4 | -1.6 |

| Business rates | 31.6 | 28.3 | -3.3 | 0.0 | -2.5 | 0.4 | -1.2 |

| Stamp duty land tax (1) | 13.4 | 15.4 | 2.0 | 0.0 | -0.8 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Air passenger duty | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Tobacco duties | 9.4 | 9.4 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | -0.3 |

| Alcohol duties | 12.7 | 12.4 | -0.3 | 0.0 | -0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Environmental levies | 10.0 | 6.6 | -3.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | -4.4 |

| UK ETS auction receipts | 1.2 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 |

| Other taxes (2) | 128.1 | 155.9 | 27.8 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 11.6 | 12.2 |

| National Accounts taxes | 792.8 | 923.7 | 130.9 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 84.3 | 43.4 |

| Interest and dividends | 26.4 | 31.1 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.7 | -0.5 |

| Gross operating surplus | 62.2 | 66.1 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Other non-tax receipts | 4.0 | 2.1 | -1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -1.9 |

| Current receipts | 885.4 | 1,023 | 137.5 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 88.0 | 44.9 |

| 1) Excludes Scottish LBTT. 2) Excludes Scottish LFT and Welsh LBT. |